WHAT IS THE CONTESTED HISTORIES INITIATIVE?

The Contested Histories Initiative (CHI) is a global effort to examine the issues surrounding statues, street names, and other historical legacies in public spaces with an aim to identify principles, processes, and best practices for decision-makers, civil society advocates, and educators confronting the complexities of divisive historical memory. In partnership with Beyond Conflict and the Institute for Historical Justice and Reconciliation (IHJR), the CHI is launching a US initiative in advance of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Building off of IHJR’s rich database of resources and case studies designed to help navigate and address contested monuments and memorials across Europe, the global CHI will, in partnership, develop additional materials which reflect the diversity of opinion across multiple disciplines and experiences in the U.S. and globally.

In 2026, the Contested Histories Initiative will bring together key stakeholders in the U.S. and globally in a national convening that seeks to center these issues on the national agenda, provide an opportunity for shared learning, and offer a set of recommendations and access to resources for communities seeking to address contested histories.

↓ Check out the first publication from the U.S. CHI ↓

The first in a series of multi-disciplinary publications and resources, this white paper provides resources for community members, researchers, funders, scholars, and practitioners to understand and engage with the role of monuments and commemoration in public life, and provides guidance for people to make practical and informed decisions about commemorative landscapes in their local communities.

↓ EXPLORE KEY LESSONS FROM THE PAPER ↓

WHY DO

MONUMENTS

MATTER?

Monuments are shortcuts for evoking identity and belonging. They are one of the most concrete tools for signaling values and declaring identities in public and function as concentrated substitutes for historical events and figures.

A monument is not merely a work of history, but a tangible and physical element in our daily lives. Monuments speak to the values and beliefs of a community. What, who, and how we memorialize matters to how community members see and understand their histories and themselves.

HOW CAN YOU UNDERSTAND A MONUMENT?

A richer understanding of what monuments are can help us gain clarity in some of the debates around commemoration. Examining these six dimensions of a monument can help us build a mutli-dimensional model of the monument and its role in public life.

POLITICAL

How are monuments connected with political orders?

Who gets to decide what belongs in public?

HISTORICAL

Whose histories are represented?

Whose are missing?

AESTHETIC

What materials are used?

Are these valuable artworks that need preservation?

ETHICAL

What ought monuments represent?

What do we do with morally problematic histories?

EPISTEMIC

What do viewers come to know through monuments?

AFFECTIVE

What feelings do these monuments evoke?

EXAMPLE: Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment in Boston, Massachusetts

The work depicts Colonel Shaw, a white commanding officer, riding on horseback while the first all-volunteer Black regiment of the Union Army marches besides him down Beacon Street. Though the monument is dedicated to the deeds of the entire regiment as well as their sacrifice during the Civil War, the two most prominent inscriptions on the memorial, located on the pedestal and the bronze sculpture, are focused on Shaw, the commander.

Consider the following epigraph: “Omnia relinquit servare rempublicam” (He left behind everything to save the Republic). The inscriptions along with the placement of Black soldiers in the background has resulted in some calling the monument problematic. Furthermore, it was not until the 1980s that the names of Black soldiers were etched into the monument.

With this background in mind, how would an examination of the Shaw Memorial yield different points of emphasis utilizing a multidimensional approach?

HOW DO PEOPLE DEBATE MONUMENTS?

Take a closer look at some of the most popular arguments made in the public arena.

HOW DO PEOPLE DEAL WITH MONUMENTS?

Eight approaches are frequently used to address conflicts about monuments and commemoration:

DEACCESSION

removal of a monument, whether temporary or permanent

Consider the case of Confederate Monuments dotted throughout the United States and their many removals. During protests against antiblack racism and police brutality, the statue of Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Virginia was defaced with graffiti before being removed from public viewing and placed into storage.

In fact, hundreds of confederate statues and symbols have been removed since 2015. However, according to the Whose Heritage? report by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) “2,089 Confederate memorials can still be found throughout the United States and its territories” (Southern Poverty Law Center, February 1, 2022).

While deaccession is frequently the focus of the monuments debate, the scale of removals in the United States is incremental at best.

RESIGNIFICATION

reshaping monuments; changing their meaning through physical or artistic intervention

Consider the artwork of Bhen Alan which utilizes weaving to provide commentary on The Hiker statue in Providence, Rhode Island. This monument commemorates American soldiers who fought in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines during the Spanish-American War and Philippine-American War.

Through binding the statue with the artist’s weaving of a traditional Filipino mat called a “baníg,” the original meaning of commemoration was transmuted into a celebration of Filipino Independence, diasporic connections, and “cultural resistance.”

This new meaning was further activated through the performance of Filipino folk dances and communal activities, including a weaving workshop, which took place around the statue.

DEFACEMENT

typically involves damaging or altering the monument significantly; immediate and direct; often done without official approval

Consider the controversy of Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park in Boston, Massachusetts. Within the park, a statue of Columbus was tagged in 2004 with the word “murderer” in 2004, beheaded in 2006, marked with the phrase “Black Lives Matter” in 2015, and decapitated once again in 2020.

These separate acts of defacement, although criminal offenses, document how celebratory estimations of Columbus are being revised. As Mahtowin Munro (Lakota) of the United American Indians of New England stated: “I don’t think that their feelings about loving Columbus should be privileged over the genuine damage that we feel as Indigenous people by going generation after generation where Columbus is held up as some kind of hero” (Cultural Survival, August 20, 2020).

Acts of defacement, while often done under the cover of night, still might indicate shifting perspectives or the emergence of previously excluded views from public appreciation.

FABULATION

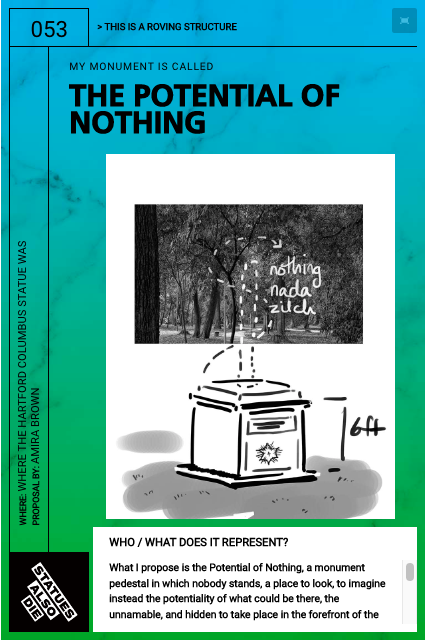

critical process in which communities and artists work both independently and together to design objects for their commemorative landscapes

Consider the public posters developed around the “Statues Also Die” exhibit in Connecticut, which sought to radically reinterpret acts of memorializing. Through an open call that asked the public to create new monuments, participants were able to submit designs and representations for the Connecticut landscape.

One proposal was called, “The Potential of Nothing,” and consisted of “a monument pedestal in which nobody stands, a place to look, to imagine instead the potentiality of what could be there, the unnamable, and hidden to take place in the forefront of the mind” (Real Art Ways, January 6, 2021).

While commemoration is typically focused on the past, collaborative or fabulated monuments can provide opportunities for reflecting about and making statements about the future as well. Fabulation can reconceive of monumentalization in brand new ways.

DESTRUCTION

demolition of a monument; permanent

Consider the toppling of a statue to King George III in New York City which occurred after the approval of the Declaration of Independence. The destructive argument can best be illustrated by this act of “symbolic regicide.”

Here the commemorative landscape was being radically remade while the country was undergoing its own transformation.

As soldiers and fervent participants dismantled this statue, they did so with the intention of never again monumentalizing their former sovereign. In fact, as U.S. Postmaster Ebenezer Hazard noted the felled statue was to be repurposed for war: “[The king’s statue] has been pulled down to make musket ball of, so that his troops will probably have melted Majesty fired at them” (National Geographic, July 1, 2020).

ABSTENTION

demolition of a monument; permanent

Consider the case of the Middle Passage and Transatlantic Slavery. While monuments to the “peculiar institution” of slavery are often underrepresented within our commemorative landscape, the slave-trade, or what poet Lucille Clifton called “a bridge of ivory,” is altogether absent.

It is for this reason that researchers, such as Ole Varmer, have argued for memorializing the Atlantic seabed: “The remains of the slave trade are tangible and intangible heritage that should be memorialized as the final resting place of the victims of the slave trade” (Duke Today, November 10, 2020).

The absence of monuments testifies to the unevenness of power and provides a good reminder that not all communities and heritages are represented in public space.

PRESERVATION

maintaining existing monuments and repairing defaced ones

Consider the case of Mount Rushmore, a monument constructed upon The Six Grandfathers (Thuŋkášila Šákpe). The preservationist argument can best be illustrated in remarks Donald Trump made during the Mount Rushmore Fireworks Celebration: “This monument will never be desecrated —these heroes will never be defaced, their legacy will never, ever be destroyed, their achievements will never be forgotten, and Mount Rushmore will stand forever as an eternal tribute to our forefathers and to our freedom” (The White House, July 4, 2020).

The preservationist argument instead of considering the historical theft of the Hé Sápa (Black Hills) and the wishes of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ for the return of their land, deem these political points to be immaterial. For once included in the commemorative landscape, the aim is only to safeguard the monument.

CONSTRUCTION

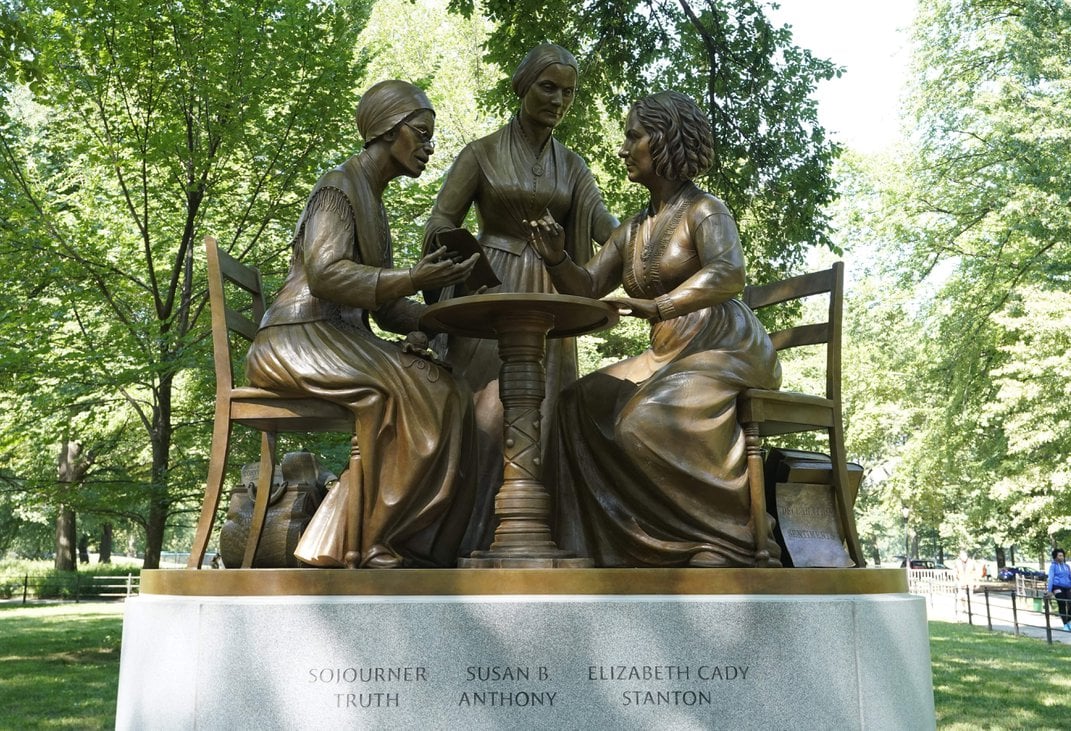

building new monuments

Consider the dearth of monuments to women in the United States. According to the National Monument Audit, only six percent of statues in the country represent women. This gendered discrepancy has resulted in renewed calls for public representation.

Take, for instance, the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument, dedicated and built to Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 2020. Meredith Bergmann, the artist who designed the statue, argued that the depiction of suffragettes would break the “bronze ceiling” around monumental inequality and provide “a positive image of diverse women working together to change the world” (Hyperallergic, August 13, 2019).

The construction of this monument was not however without some controversy. Since the original design only included Anthony and Stanton many felt that the project was whitewashing and erasing the contributions of Black women. It is important to remember that construction is not a foolproof method.

HOW CAN YOU APPLY THESE SKILLS IN YOUR COMMUNITY?

More tools to help you address contested histories and monuments in your communities are on their way!

Subscribe to get notified when more materials and resources come out from the U.S. Contested Histories Initiative:

WANT MORE?

Continue exploring debates around contested histories and practice your new skills using these great resources from our partners: